It’s not every day you discover a bit of family history you share with the British Prime Minister, but it happened to me late last summer.

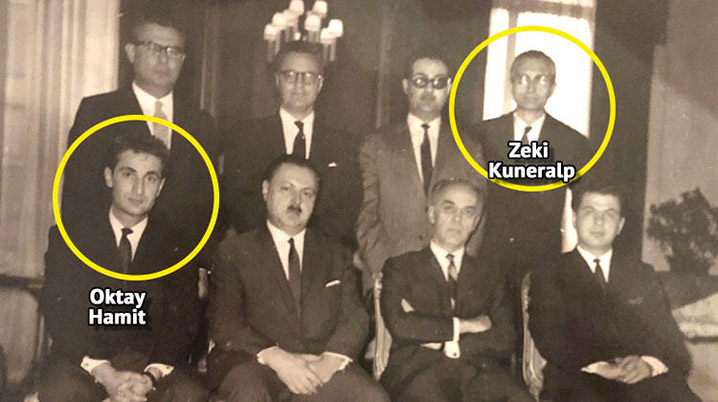

I was flicking through family photo albums with my father, Oktay Hamit, when I came across a large black and white one of him and seven other men. I recognised a few of the faces in the photograph: Ahmet Gazioğlu, top row, second from the right, was the Turkish Cypriot Representative to London in the 1960s. Also Fikret Derviş, the uncle of best-selling author Sibel Hodge and a future president of the Council of Turkish Cypriot Associations in Britain (CTCA UK), on the far right of the front bottom row.

My father, who was seated on the far left of the bottom row in the picture, pointed to the gentleman standing in the top right: Zeki Kuneralp. I didn’t recognise his face or name.

My father said he had been the Turkish Ambassador to London in 1964, when the photo was taken, and casually mentioned he was Boris Johnson’s uncle. My eyes opened in amazement and I stared more closely at the photo.

“As the ambassador, why was he standing and not seated in the middle?” I asked my father.

“Because he was a very decent man who didn’t covet the limelight,” came the reply. “He placed a lot of importance on young people, so although we urged him to sit at the front, Zeki Bey said ‘You young people are more important, you are the future’, so he preferred to stand and let us sit,” my dad added.

I was astonished. Given the patriarchal nature of Turkish society, where our male elders always dominate, such modesty was indeed a rare thing.

I enquired how the photo came about, and it was through this exchange I realised Boris’ uncle had played a pivotal role in helping Turkish Cypriots at one of the most critical times in our recent history. It also turns out that Ambassador Kuneralp was a most brilliant diplomat who endured tragedy at several points in his life.

Who was Zeki Kuneralp?

He was born in Istanbul in October 1914, and was the son of Ali Kemal – Boris Johnson’s great grandfather – and Kemal’s second wife Sabiha Hanım (Boris’s family line is through Ali Kemal’s first marriage to Winifred Brun).

Zeki Kuneralp was raised in exile by his mother in Switzerland after his father, a journalist and former Ottoman Minister of the Interior, was lynched and killed in 1922.

With the Ottoman Empire collapsing, Ali Kemal had advocated the Turks capitulate to British rule, which was seen as treason by the Young Turks. In 1919, when he was a Minister, Ali Kemal also ordered the arrest of one Mustafa Kemal, later known as Atatürk, who was leading the Turks in the War of Independence. With the tide turning in the Turks’ favour, Ali Kemal was ordered to face trial on charges of treason a few years later, but he was abducted from a barbers shop in Istanbul, and killed by a mob for his alleged treachery.

Like his father, Zeki Kuneralp was academically gifted. He gained a Law doctorate from the University of Bern in 1938 and was keen to return to his native Turkey, but was advised not to by family and friends due to his father’s disgraced background. Yet Kuneralp would not be deterred and was keen to serve his country. He lobbied and eventually obtained the express permission of President İsmet İnönü to return and apply to join the diplomatic corps.

Kuneralp entered the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1942, and went on to serve in posts across Europe. He was appointed Turkish Ambassador to Switzerland, the United Kingdom (1964-66 and 1969-1972) and Spain, as well as twice serving as Secretary-General of the Foreign Ministry.

He survived an assassination attempt by Armenian terrorist group Asala, which sadly claimed the lives of his wife Necla and her brother in Madrid in 1978.

Kuneralp retired, in part due to ill-health, in 1979, and turned his attention to writing instead. His autobiography Sadece Diplomat was translated into English in 1992, while others of his books are considered important sources of twentieth century Turkish history. He died in Istanbul on 26 July 1998, leaving two sons Sinan, a leading Istanbul publisher, and Selim, who followed in his father’s footsteps and became a diplomat.

Zeki Kuneralp’s vital role in Turkish Cypriot history

On 21 December 1963, three years after Independence, the Cyprus Conflict broke out. As the whole world shut down for Christmas, Greek Cypriots mounted a bloody coup that lasted ten days. 133 Turkish Cypriots were murdered, and thousands were made homeless, as their former partners installed themselves as the sole government of Cyprus.

As news of the bloody coup reached London, Turkish Cypriots were furious and fearful. Not all homes had phones and details of events in Cyprus were being gleaned in a haphazard manner. My father, then a student studying civil engineering in London, and his friends were among the organisers of the large demonstration in central London on 27 December.

They set up a crisis desk in the Kıbrıs Türk Cemiyet building in D’Arblay Street, Soho. My dad said he didn’t leave the desk for 48 hours, such was the frenzy among the people to learn the fate of their loved ones. Young Turkish Cypriots quickly formed an Aid Committee, to raise money and collect essential items, such as clothes and blankets, for the many thousands left homeless in the bitter cold winter months.

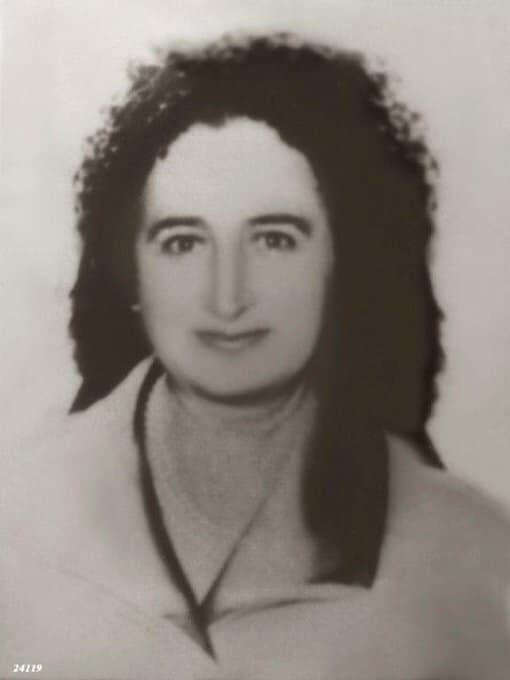

My father was elected the head of the group, while my mother, Suzan, who had been working in the Cyprus High Commission in London when she heard her elder brother Fuat had gone missing, was elected the head of the women’s equivalent (it was at this time that my parents met, fell in love and later got married, but that’s a tale for another day).

The two aid committees worked round the clock, organising collection boxes, and holding meetings and publishing weekly bulletins to update people on events back home, and the fate of those who had been reported missing in Cyprus.

Early in 1964, Zeki Kuneralp arrived as the new Turkish ambassador to London. Turkey and Britain, along with Greece, had been Guarantor Powers in Cyprus since 1960; but the carefully-constructed power-sharing agreement between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots now lay in tatters.

The Turkish community in Cyprus was under siege and was desperately trying to hang onto the fishing village of Erenköy in the northwest of the island. To a man, they knew that holding on to this territory, with its 5 km long coastline and sea port – the only one in Turkish Cypriot hands – was of paramount importance to ensure essential supplies from Turkey got through. They were also vastly outnumbered and outgunned, with enemy forces encircling them on land.

Turkish Cypriots from neighbouring villages, such as Bozdag (Aytotoro), Mansur (Mansoura) and Selcuklu (Selaintapi), collectively known as the Dillirga (Tillyria) area, numbered 1060 in 1963. Many fearing Greek Cypriot attacks fled to Erenköy for their safety.

Turkish Cypriot students abroad, including those in Britain, were desperate to return home and help the fight.

Ambassador Kuneralp invited my father and others from the Turkish Cypriot Aid Committee to the Embassy. Together, they reviewed the situation and its demands. The community in London had raised money to buy radio equipment to help set up a new station in Anamur, in southern Turkey, so Turkish Cypriots could broadcast freely. “The ambassador arranged for the transmitter and other kit to be immediately dispatched to Turkey. This is how Bayrak Türk Radyo started.”

“Kuneralp Bey was great for morale,” my dad explained. “It was such an emotionally charged time, but he would always keep our thoughts calm and positive. He regularly praised our volunteer efforts, and added us to the embassy’s ‘protocol’ list, so we would get invitations to key events and receptions at the embassy, helping to raise the community’s profile. He was also a superb diplomat.”

“We were so proud to have such a dignified and knowledgeable man represent us. He articulated our concerns and issues so well to the British press and politicians, countering the Greek Cypriot narrative of events.”

The ambassador and his staff were in daily contact with the Turkish Cypriot UK Representative Gazioğlu. While the Turkish Embassy was not involved in the actions of Turkish Cypriots in London, they would keep a close eye on everything and offer support where appropriate.

The Aid Committees maintained pressure on the British government with mass rallies, while keeping the community informed through weekly cinema screenings, which brought the community together. Their contacts through the Embassy helped with fundraising appeals to other Muslims in Britain, such as the Pakistani community.

By 5 August 1964, military units led by experienced terrorist EOKA leader General George Grivas had intensified their attacks on Erenköy, determined to bomb or starve the Turkish Cypriots out.

Along with heavy artillery on land, Grivas was also able to call upon gunboats from Greece to join Cypriot naval patrol boats, then in Greek Cypriot hands, to shell the village. For several days they pummelled Erenköy with rockets, mortar shells and machine guns. It was difficult to believe Turkish Cypriots could survive the relentless bombing.

It was against this backdrop that Turkey, through its right as a Guarantor Power of Cyprus, decided to intervene by sending aerial support to the besieged villagers. A small squadron led by pilot Cengiz Topal, who died in action, left Turkey on 8 August. A day later, Turkey significantly increased its aerial bombardment of the Dillirga region, sending 64 aircraft and a clear warning to Greek Cypriots that this was one battle they could not win. The show of force worked. Twenty-four hours later a ceasefire was declared.

Greek Cypriots mounted a big protest outside the Turkish Embassy in London. It was countered massively by the Turkish Cypriot community, fiercely loyal to Kuneralp and Turkey for its vital intervention.

This was a major turning point, and while it did not end the conflict, Turkey had given important respite to Turkish Cypriots and ensured they retained control of the strategic port at Erenköy. The world was also made aware of the terrible plight of Turkish Cypriots, which was covered extensively in British and other international press.

The siege of Erenköy stands as proof that Greek Cypriot brutality towards Turkish Cypriots began a whole decade before ever Turkey’s Peace Operation became necessary in 1974, to rescue thousands of civilians from the sword of EOKA after ten years of bloody persecution. To that end, Ambassador Kuneralp’s role was crucial, “a lifeline” my father said, for Turkish Cypriots.

This article was first published in T-VINE Magazine Issue 12, Dec. 2019