“Life can best be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards”

Too much time has been spent in technicalities, in committees, in deadlines that never seem to be reached, but keep being moved forward to another deadline, which only prolongs the agony. The players change, they grow old, they even die, but for this island, the game is still played in the same way. The facts are the same, the solution is obvious. Above all, no-one, absolutely no-one, is rediscovering America again!! It’s all been said before. Believe me!! Only the speakers, the sentences and the expressions change.

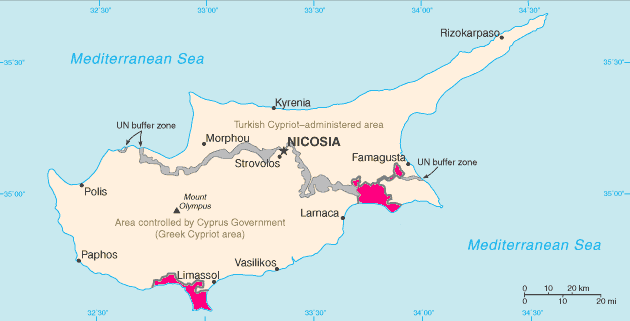

We all know about the Cyprus Problem. Don’t we? At least all Cypriots do. Depending on where one looks from, the Greek or the Turkish side, each have their own version. Their own reality, suffering and truth. Remember, this has been going on for decades and decades. The Turkish Cypriot state is considered as “illegal.” i.e. non-existent in international law. That is the international community’s starting point, so understandably how could they assess our status and conclude in any other way.

Please be informed, this is not a political article about “the problem”. It’s about certain judicial findings that changed the landscape for Turkish Cypriots on the international arena and paved the way for the acceptance of Turkish Cypriots as a valid entity (even if only locally) with a solid legal and judicial foundation in place to be relied on for when the time comes for a resolution.

Findings that set a precedent about why there *is* Justice and the Rule of Law in northern Cyprus. A finding that no legal country in the world (as far as I am aware of) has had recorded about their court system in a qualified judgement. Imagine: a legal, independent functioning and effective judicial system existing in a state recognised as being “illegal” by the international community. Quite a feat for Turkish Cypriots, perhaps.

Don’t forget Turkish Cypriots are like pawns in a chess game, used for super political bargaining, so we need to really understand the importance of what the Turkish Cypriot legal process has bestowed upon us, and firmly hold on to protect this gift at all costs.

Understand backwards, live forwards

As with everything else in Cyprus, importance is paid to political gains, but legal gains don’t actually matter within the whole Cyprus context. Politics always come before law, law is then used; it follows to ‘legalise’ those political situations. But in this case, it has been the reverse.

No Turkish Cypriot even mentions it, maybe because they may not be aware of its implications. But, as the facts of the game and actions show, the south of the island knows. I believe they just wish it to disappear, pretend it doesn’t exist, cover it up, by putting their heads in the sand. There is constant distortion. Yet, it is up to Turkish Cypriots to make sure that the rule of law is preserved.

The Cyprus Problem has been stuck in the past for decades and generations. So why has this finding been put aside? We fail to consider exactly why the international community is still holding on to and open to a federal system in Cyprus. Can this ‘fact of legitimacy’ be one reason why we are still around as a people, why people still talk with us?

1999-2001 – and the way ahead

Zaim Necatigil is a leading Turkish Cypriot lawyer in Cyprus and one of the few legal minds who comprehended the significance of the findings I am about to mention. In fact he was directly involved in the process. Writing in an article on the findings in the Loizidou case, he saw the reality long before the Commission or Court did:

“The Court failed to examine the true governmental position in North Cyprus as it actually existed at the time of the judgement. If this had been properly done, the Court would have been bound to find, as the Commission found in the Chrysostomos and Papachrysostomou case, that the Greek Cypriot government in South Cyprus had not exercised authority over the Turkish Cypriots since December 1963.”

“Further, it would have found that the people of North Cyprus have been governing themselves in an orderly manner in accordance with democratic standards, in particular, as laid down in Article 3 of the First Protocol to the Convention, and that there existed in fact an administration and a judiciary, as well as, a legislature capable of making laws—that is to say, the very ingredients of statehood.”

In the late 1990’s, along with other witnesses, I was called to give evidence in the 4th Interstate application Cyprus v Turkey, 25781/94 before the then European Human Rights Commission (before it was abolished). The case related to claims of continuing violations of certain articles of the Human Rights Convention against Turkey. These complaints also included alleged violations of the rights and living conditions of enclaved Greek Cypriots in northern Cyprus.

ECHR Grand Chamber concluded an independent and impartial court system exists in the TRNC

When the EHR Commission came to Cyprus to conduct the hearing on the spot, at the Ledra Palace building, on my invitation they visited the Turkish Cypriot courts to get a first hand view of exactly the place judges worked in etc. They came to visit under the Commission President, Stefan Trechsel. They saw the courts in action. In brief, this was later effective in securing the said finding of the Commission.

The case went even further; to the Grand Chamber of European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Details are not necessary. The evidence given to the Human Rights Commission and to the Court proved before the Council of Europe human rights bodies and to the rest of the world in a Grand Chamber landmark decision on 10 May 2001 and from there on reiterated in other decisions related to Cyprus issues, that an independent and impartial court system exists in the TRNC:

“Para 233 … Furthermore, a court or tribunal is characterised in the substantive sense of the term by its judicial function, that is to say determining matters within its competence on the basis of rules of law and after proceedings conducted in a prescribed manner. It must also satisfy a series of further requirements – independence, in particular of the executive; impartiality; duration of its members’ terms of office; guarantees afforded by its procedure – several of which appear in the text of Article 6 § 1 (see, among other authorities, the Belilos v. Switzerland judgment of 29 April 1988, Series A no. 132, p. 29, § 64)……………..

“237… The Court observes from the evidence submitted to the Commission (see paragraph 39 above) that there is a functioning court system in the “TRNC” for the settlement of disputes relating to civil rights and obligations defined in “domestic law” and which is available to the Greek-Cypriot population. As the Commission observed, the court system in its functioning and procedures reflects the judicial and common-law tradition of Cyprus (see paragraph 231 above). In its opinion, having regard to the fact that it is the “TRNC domestic law” which defines the substance of those rights and obligations for the benefit of the population as a whole it must follow that the domestic courts, set up by the “law” of the “TRNC”, are the fora for their enforcement. For the Court, and for the purposes of adjudicating on “civil rights and obligations” the local courts can be considered to be “established by law” with reference to the “constitutional and legal basis” on which they operate…………………………

“239… The Court notes that the applicant Government contests the independence and impartiality of the “TRNC” court system from the perspective of the local Greek-Cypriot population. However, the Commission rejected this claim on the facts (see paragraph 231 above). Having regard to its own assessment of the evidence, the Court accepts that conclusion.

“240. For the above reasons, the Court concludes that no violation of Article 6 of the Convention has been established in respect of Greek Cypriots living in northern Cyprus by reason of an alleged practice of denying them a fair hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal in the determination of their civil rights and obligations…”

As a result of this, the ECHR did not find a violation against Turkey of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights in relation to rights to a fair and impartial trial. The decision expressively confirmed the effective functioning of a Rule of Law system within the TRNC. The way had also been laid for the decision in the Xenides-Arestis cases followed by the momentous decision in Demopoulos.

In the face of more overbearing political considerations, not many people have been made aware of the importance of this legal finding. A finding that is recorded in a judicial pronouncement of an international Court; the presence of functionality, of an effective, independent, unbiased judicial and legal system existing at the domestic level within the TRNC – an “illegal state” – even though considered as “a subordinate local authority” of Turkey by the so-inclined international community.

In other words, in the Turkish Cypriot courts, justice for all who seek it can still be found and served through the work of independent, impartial judges. No-one is perfect, including judges, but exceptions, as in any legal system, are not the rule in northern Cyprus. Any weaknesses or defect in such a system, in my humble opinion, is a result of the political climate and circumstances under which the courts in the North have to function, as best they can.

“A stable rule of law is the backbone of any democratic State”

The finding of an effective and functioning legal and judicial system is why Turkish Cypriots are still able to build on their internal legal, administrative and political institutions and processes. It may be small and insignificant and taken for granted in some circles, but to a people that are striving for acceptance, it should not be underestimated. A stable rule of law is the backbone of any democratic State.

The rule extends to all areas where a need to rely on legal or judicial remedies from the TRNC are called for. An example of the trust placed in this fact can also be seen from the recent UK High Court ruling that points out that suspects who are refused to return to Britain can now be prosecuted in North Cyprus.

There is trust in the TRNC legal system. That is, it is now recognised that before any kind of application can be made to any other international court, such as the ECHR, local remedies in the North have to be exhausted by all. This includes the Immovable Property Commission (IPC) as an established and approved mechanism offering an alternative remedy for the largest area of breach of property rights in North Cyprus, namely the rights of Greek Cypriots with title deeds dating back to 1974.

Appeals from the IPC go the Turkish Cypriot Supreme Administrative Court for final adjudication. This mechanism for “exhausting domestic remedies” before applying to ECHR became legally established.

How then, if not for the recognition of the effective North Cyprus legal system finding, could the Demopoulos j0udgement of 2010 and those that followed come into being or have a basis? The outcome of the assessment of the effectiveness of the IPC by the ECHR in the Demopoulos case has been the most substantial development in the legal field in North Cyprus and, in effect, a measure of the current respect for human rights relating to property.

At the execution stage of the 4th Interstate judgement, I took part as an expert in the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers /Delegates Human Rights meeting (DH) for over a period of five years, going to Strasbourg about six times a year. Despite all the odds, I reiterated over and over in so many different ways, the validity and independence of the northern Cyprus Anglo-Saxon legal and judicial system and its difference from the legal system of Turkey. At these meetings, the task was related to the improvement of the living conditions by the authorities in charge for Greek Cypriots living in the “enclaved north” region of Karpaz. The right to receive an education related to schooling system for the Greek Cypriots in Karpaz, freedom of religious practice, ownership of property issues and the use of military courts to try Turkish Cypriots.

Meticulous preparation and liaising with the Turkish Delegation, relevant TRNC authorities secured necessary legislative amendments and technical procedures to satisfy DH Committee members and move on.

The Missing Persons issues still continues before the Committee today, but by the time I concluded my responsibilities in the Committee in 2005, closure of certain instances giving rise to HR violation findings against Greek Cypriots living in northern Cyprus, such as those relating to religious freedoms (European Convention on Human Rights Art.9) freedom of movement (Art.8), education (Art.10) and the composition of Turkish Cypriot military courts (Art.6.) had been achieved. These freedoms are now fully secured within the Turkish Cypriot legal system in the north of the island.

“recognition” and “legitimacy” are two different things

The confirmation of impartial and fair judges in the North, was also instrumental in securing my eligibility to sit as an “ad hoc” judge on the Bench of the European Court of Human Rights in a case of Missing Persons in Cyprus in the Varnava & Others, designated by Turkey, despite Greek Cypriot objections; a humble honour and privilege, which crowned my long professional life.

As Necatigil also points out, this is why the State in the northern part of the island though seen “illegal” under international provisions, is nevertheless legitimate within her own domestic legal system. Meaning “recognition” and “legitimacy” are two different things.

The State in the North is recognised as being “internally” (domestically) legitimate, effective and fair. There should be no derogation from this. Turkish Cypriots in all spheres must strive to maintain a high quality of the rule of law, respect the judiciary and be responsible in carrying it even further until the “external” (international) political recognition is also “legitimized”. Otherwise, what is the alternative?

Gönül (Başaran) Erönen is the first female judge on the island of Cyprus, a former Justice of Supreme Court of Northern Cyprus and “ad hoc” judge of the European Court of Human Rights. She is also a member of the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) and judicial expert in the International Legal Assistance Consortium (ILAC) Syria justice sector assessment mission, 2016. She is a barrister, with an M.A. in International Relations.

Notes: 1) Main photo of TRNC Justice Department. Photo © Steffen Löwe / Wikimedia Commons

2) “Life can best be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards” – quote by Søren Aabye Kierkegaard –Danish philosopher (1813-1855)

3) The article drew on a number of sources including:

i) Zaim Necatigil, “Perceptions”- Journal of International Affairs, September – November 1999 Volume IV – Number 3 – “Judgement of the European Court of Human Rights in the Loizidou Case: A Critical Examination”, page 4.

ii)4th Interstate Application: Cyprus v Turkey (25781/94) Grand Chamber Judgement -10 May 2001, Para 228 – 240; See also para 406- 417 Commission report 1993, para 439-447 Commission Report 1993-finding of no violation of Article 6 ECHR.

iii) See Emine Çolak “Kıbrısta Mülkiyet Hakları”, ktihv.org/raporlar/kibrista_mulkiyet_haklari

iv) ECHR Law 67/2005 –reconstructed the IPC and made it an “effective domestic remedy”.