Fifty five years ago today, the United Nations (UN) Security Council passed a resolution, the ramifications of which continues to be felt decades later.

Three years after the independence of Cyprus from British rule, leaders of the Greek Cypriot community initiated their notorious Akritas Plan, which aimed to overthrow the power-sharing arrangement between themselves and the numerically smaller Turkish Cypriot community in the Republic of Cyprus, and instead form political union with their ‘motherland’ Greece (‘Enosis’).

In an era preceding the internet and mobile communications, Greek Cypriots took advantage of the world shutting down to celebrate Christmas and the New Year, and seized power.

This brutal coup, dubbed by international media as ‘Bloody Christmas’, started on 21 December 1963 and during a 10-day period, resulted in 133 Turkish Cypriots being murdered and some 20,000 Turkish Cypriots made homeless.

Turkish Cypriot legislators and senior civil servants were denied access to the Cypriot Parliament and their workplaces, often at gunpoint.

As the Turkish side tried to resist the coup, the conflict escalated and quickly enveloped the whole island.

When details of events in this strategically important corner of the Eastern Mediterranean reached international shores, the world tried to intervene.

Efforts to mediate between the two Cypriot communities failed to generate a positive outcome, prompting the UN to offer to send an international peacekeeping force to the island. Both sides agreed.

The UN’s Security Council sought to ratify this arrangement and at its 1102nd meeting, held on 4 March 1964, Security Council members unanimously passed Resolution 186. Its full text is given below.

While the intentions of the UN were good, this poorly drafted resolution inadvertently changed the balance of power on the island, and ensured the Cyprus Conflict would continue long after the guns stopped firing.

The Cyprus Constitution and the treaties which established the Republic of Cyprus in 1960 clearly set out the power-sharing relationship between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots as ‘political equals’.

At the time of UN Resolution 186, “the Government of Cyprus” was entirely in Greek Cypriots hands, so by using this term in the text, the international community appeared to validate this state of affairs, while relegating the Turkish Cypriots to the status of a mere “community”.

In one fell swoop, this UN document not only gave Greek Cypriots the green light to continue as the sole recognised authority on the island, but also deprived Turkish Cypriots of their inherent legal and political rights.

For Turkish Cypriots, UN Resolution 186 is an unmitigated disaster.

4 March 1964 marks the date Turkish Cypriots first became embargoed: denied a political seat at the UN and a say in the future of their homeland. They are barred from direct trade, travel and communications with the rest of the world, and banned from participating in all UN-linked international political, cultural or sporting events, institutions and platforms.

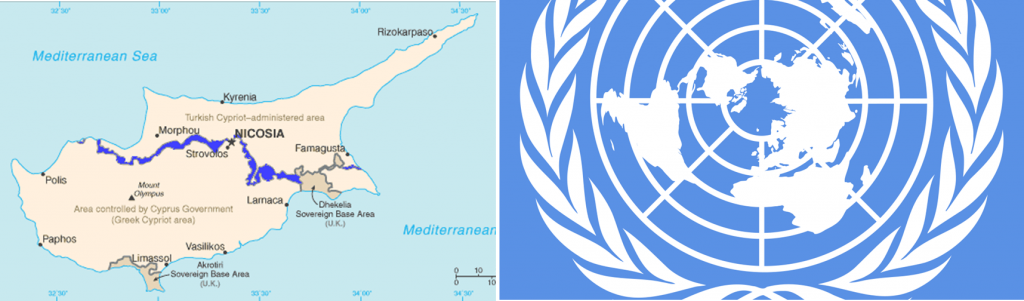

This oppressive state of affairs improved markedly when Turkey intervened in the summer of 1974 and divided the island into two ethnic zones: the Turkish north and the Greek south. Instead of being at the mercy of Greek Cypriots every time they stepped outside of their enclaves, Turkish Cypriots are now free to roam in North Cyprus and to access the rest of the world via Turkey.

Efforts to reach a permanent political solution based on parity between the two sides, however, remain elusive. Greek Cypriots continue to use their internationally recognised status to deny Turkish Cypriots their basic human rights in the hope that one day they will capitulate and relinquish their coveted political equality and instead accept ‘minority’ status.

And as long as the rest of the world goes along with this sham, allowing Greek Cypriots sole rights to the Republic of Cyprus, they can continue to use this unfair advantage to maintain the embargoes by insisting members of the international community do not recognise or deal directly with their former partners.

In 2004, myself and two friends in London formed Embargoed! – a human rights group that aimed to overturn this state of affairs. Supported by a mass of Turkish Cypriots in North Cyprus and Britain, we used a wide range of tactics to raise awareness about the plight of Turkish Cypriots.

Actions such as ‘Balls to embargoes – footballers strip for their rights’ captured international media attention as it highlighted the absurdity of the FIFA ban on even friendly international football matches. Our Gagged in Brussels protest saw hundreds of Turkish Cypriots from North Cyprus and the Diaspora come together outside the EU Commission in Brussels to demand political representation for Turkish Cypriots.

Embargoed!’s patron, fashion designer Hussein Chalayan MBE took the issue to Paris Fashion Week by designing ‘rotting lemons’ t-shirts to make the point that under embargoes, most of North Cyprus’s fresh produce remains unsold, left to rot away on trees. It was also a powerful metaphor for generations of Turkish Cypriots unable to fulfil their potential due to their international isolation.

Today, the group continues to lobby guarantor Britain, the EU and other international bodies about the injustices Turkish Cypriots still face more than half-a-century after the outbreak of the Cyprus Conflict.

While there is now global awareness and sympathy towards Turkish Cypriots, the impact of UN Resolution 186 still looms large in determining the response of governments to the international isolation of this peaceful community.

When Embargoed!’s current chair Fahri Zihni asked his local MP Daniel Kawczynski to raise the embargo issue with the British Foreign Office last year, the reply from Minster for Europe Sir Alan Duncan was telling:

“The UK recognises only one Cypriot state, the Republic of Cyprus and only one government as the sole legitimate government.”

Five generations of Turkish Cypriots have now lived under embargoes. It seems that until we can overturn UN Resolution 186, many more are destined for the same.

UN Resolution 186 of 4 March 1964 [S/5575]

The Security Council,

Noting that the present situation with regard to Cyprus is likely to threaten international peace and security and may further deteriorate unless additional measures are promptly taken to maintain peace and to seek out a durable solution,

Considering the positions taken by the parties in relation to the treaties signed at Nicosia on 16 August 1960,

Having in mind the relevant provisions of the Charter of the United Nations and, in particular, its Article 2, paragraph 4, which reads: “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use, of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations “,

- Calls upon all Member States, in conformity with their obligations under the Charter of the United Nations, to refrain from any action or threat of action likely to worsen the situation in the sovereign Republic of Cyprus, or to endanger international peace;

- Asks the Government of Cyprus, which has the responsibility for the maintenance and restoration of law and order, to take all additional measures necessary to stop violence and bloodshed in Cyprus;

- Calls upon the communities in Cyprus and their leaders to act with the utmost restraint;

- Recommends the creation, with the consent of the Government of Cyprus, of a United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus. The composition and size of the Force shall be established by the Secretary-General, in consultation with the Governments of Cyprus, Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The Commander of the Force shall be appointed by the Secretary-General and report to him. The Secretary-General, who shall keep the Governments providing the Force fully informed, shall report periodically to the Security Council on its operation;

- Recommends that the function of the Force should be, in the interest of preserving international peace and security, to use its best efforts to prevent a recurrence of fighting and, as necessary, to contribute to the maintenance and restoration of law and order and a return to normal conditions;

- Recommends that the stationing of the Force shall be for a period of three months, all costs pertaining to it being met, in a manner to be agreed upon by them, by the Governments providing the contingents and by the Government of Cyprus. The Secretary-General may also accept voluntary contributions for that purpose;

- Recommends further that the Secretary-General designate, in agreement with the Government of Cyprus and the Governments of Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom, a mediator, who shall use his best endeavours with the representatives of the communities and also with the aforesaid four Governments, for the purpose of promoting a peaceful solution and an agreed settlement of the problem confronting Cyprus, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, having in mind the well-being of the people of Cyprus as a whole and the preservation of international peace and security. The mediator shall report periodically to the Secretary-General on his efforts;

- Requests the Secretary-General to provide, from funds of the United Nations, as appropriate, for the remuneration and expenses of the mediator and his staff.