Until 20 July 1974, the so-called ‘Cyprus Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ of the so-called ‘Republic of Cyprus’ didn’t care a bit for International Law. Otherwise, by the summer 1965, the 1960 Constitution that formed the power-sharing Republic of Cyprus between Greek and Turkish Cypriots could have been fully restored. But Greek Cypriots preferred to continue with their own de-facto and unlawful rule.

Since 1964, Greek Cypriots are using the Doctrine of Necessity as a magical “get-out-of-jail” card to mask the illegality surrounding the Republic of Cyprus, after forcing out Turkish Cypriots from the power-sharing arrangements in December 1963.

This article aims to demonstrate that the use of this mask to try to legitimise the Greek Cypriot dominated rule in Cyprus is itself unlawful.

In any given democratic society, the rule of law normally means individuals can do as they like unless there is a law that says they can’t. For governments, however, they can do nothing unless there is a law that says it can.

The Doctrine of Necessity is the basis on which extra-constitutional actions by an administrative authority occur that are designed to restore order or to attain power on the pretext of stability. In this context, such actions are lawful, even if they contravene the established constitution, laws and norms.

However, under International Law, a State cannot invoke the Doctrine of Necessity if that State has substantially contributed to the situation of necessity, since a State cannot take advantage of its own wrongdoing.

Direct involvement of the organs and the key authorities of the State of Cyprus, in the planning and conduct of violence, from late 1963 through to 1974, against its Turkish Cypriot citizens is a well-established fact, backed up with incriminating documentary evidence in political papers, United Nations reports and international media coverage.

Through this direct involvement, not only can one prove that the State of the Republic of Cyprus had substantially contributed to the creation of this “situation of necessity”, but that it also took advantage of its own wrongdoing by transforming the State in Cyprus into a wholly Greek State, which is expressly forbidden in the 1960 Treaties and Constitution that established the Cypriot Republic.

The direct involvement of the Greek Cypriot President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios, the Interior Minister of Cyprus, the President of the House of Representatives of Cyprus, the Minister of Labour of Cyprus, the top military commanders and senior members of the Cyprus Police Force – all Greek Cypriots and who authorised such actions – have been proven beyond any doubt.

The Greek Cypriot-controlled Republic of Cyprus was directly responsible for the imposition of an environment of complete insecurity upon Turkish Cypriots by random and targeted kidnappings, widespread murders and massacres that started with a 10-day killing spree known as ‘Bloody Christmas’ late in December 1963.

Within weeks of Bloody Christmas, one percent of the entire Turkish Cypriot population had been killed, and a quarter of them became refugees or internally displaced persons.

These events destroyed the trust between the two communities and made a mockery of the Cyprus Constitution. It deliberately created and sustained an environment of heightened insecurity for Turkish Cypriots, which in turn prevented this vulnerable minority from participating in the normal functioning of the State.

By the end of April 1964, while violent attacks by State forces on the Turkish Cypriot community was continuing, the Republic of Cyprus, now under de-facto full control of Greek Cypriots, used this prolonged absence of Turkish Cypriot civil servants as a pretext to dismiss all of them from their public functions.

“under international law, a State cannot invoke the Doctrine of Necessity if that State has substantially contributed to the situation of necessity, since a State cannot take advantage of its own wrongdoing”

A few months later, under curious circumstances, the Greek Cypriot-controlled Republic of Cyprus invoked the Doctrine of Necessity as a mask to hide the illegality of running a bi-communal State without Turkish Cypriot participation. They used this doctrine to claim “temporary” legitimacy over exclusive Greek Cypriot control of the State of Cyprus.

The curious circumstances under which the Doctrine of Necessity was first used came about in the legal case of the Republic of Cyprus vs Mustafa Ibrahim in 1964, where the “judgment” was finally handed down on November 10, 1964, by an illegally restructured “new” Supreme Court, which was composed wholly of Greek Cypriot judges.

This new Greek Cypriot-controlled Supreme Court bypassed the constitutionally binding need for the participation of Turkish Cypriot judges. Essentially, this Court was now sitting in judgment of its own cause, which is nothing but a blatant and clear case of a conflict of interest.

In fact, this new Greek Cypriot staffed Supreme Court had a direct self-interest in the outcome of its own ruling. It was no longer impartial to the interests of Greek Cypriot community, who set out to control the State, and could only be partial to the interests of the Turkish Cypriot community.

After the “manufacturing” of the above legal precedent, the Doctrine of Necessity was used as a permanent legal tool to “temporarily” suspend all the articles of the Cyprus Constitution that required Turkish Cypriot political participation in the bi-communal aspects of the State.

By the end of autumn 1964, an unlawful “legal” way was hence found, providing a convenient way to avoid implementing the Cyprus Constitution as far as it concerned the rights of the Turkish Cypriots.

This roadmap for non-implementation of the Constitution was drawn following the recommendation contained in a legal counsel given to the Cypriot President, Archbishop Makarios, by a British legal expert back in the summer of 1963, outlining what the Cypriot State would have to do to avoid legal intervention by Türkiye, a Guarantor Power of Cyprus.

“the Doctrine of Necessity was first used in the case of the Republic of Cyprus vs Mustafa Ibrahim in 1964, where the judgment was handed down by an illegally restructured “new” Supreme Court composed wholly of Greek Cypriot judges”

Yet it is unlawful, under International Law, for the State of Cyprus to invoke the Doctrine of Necessity when that State, through its Officers and Institutions directly contributed to the creation of the conditions of ‘necessity’, which were subsequently used as a pretext for the invocation of that principle.

Furthermore, in the summer of 1964, it was by no means clear that the Republic of Cyprus could invoke the Doctrine of Necessity in a unilateral manner under the 1960 Cyprus Treaties, without the express agreement of the other concerned parties, namely Turkiye, Great Britain and Greece.

The result has been that the Doctrine of Necessity, after its illegal invocation, has been practiced in Cyprus unlawfully as if it were a natural state of affairs, when it was only ever intended as a temporary emergency measure. This situation has lasted well past its sell-by-date and instead, the Greek Cypriots made it a permanent fixture.

3 ways the Doctrine of Necessity by the State of Cyprus is unlawful

In summary, the invocation of the Doctrine of Necessity by the State of Cyprus is unlawful in three ways:

- A State cannot implement such an invocation if that very same State contributed to the creation of the conditions of necessity, which were later claimed as justification by the same State for the invocation of Doctrine of Necessity.

- The initial legal case used as a precedent for future acts of necessity, was taken up by a “court” which was itself formed by an illegal act that was contrary to the Constitution. It was this illegal “court” that decided whether the “court” itself was legal or not!

- Under the 1960 Cyprus Agreements, which form part of the International Law, the Republic of Cyprus could not act in a unilateral way in rejecting its obligation to respect in full the Cyprus Constitution.

Despite the above clear illegalities, the Greek Cypriot Government of the Republic of Cyprus has, nevertheless, successfully asserted itself as legitimate both internally and externally even though the issue is not free of difficulty, since the participation of Turkish Cypriots is essential.

Internally, the Greek Cypriots try to claim the lack of Turkish Cypriot participation does not render its government unlawful because of the “temporary” and highly expedient Doctrine of Necessity, but they fail to admit that the invocation of this doctrine was itself unlawful and that such a doctrine cannot stay in use indefinitely.

In their efforts to convert the Republic of Cyprus into an Hellenic State, Greek Cypriots were aided by the fact that the international community has failed to challenge them over what the world ostensibly regards an “internal” matter, even though strict adherence to the Constitution was undertaken by the Republic of Cyprus as an international obligation, violation of which was subject to corrective action by Guarantor powers as defined in the Treaty of Guarantee.

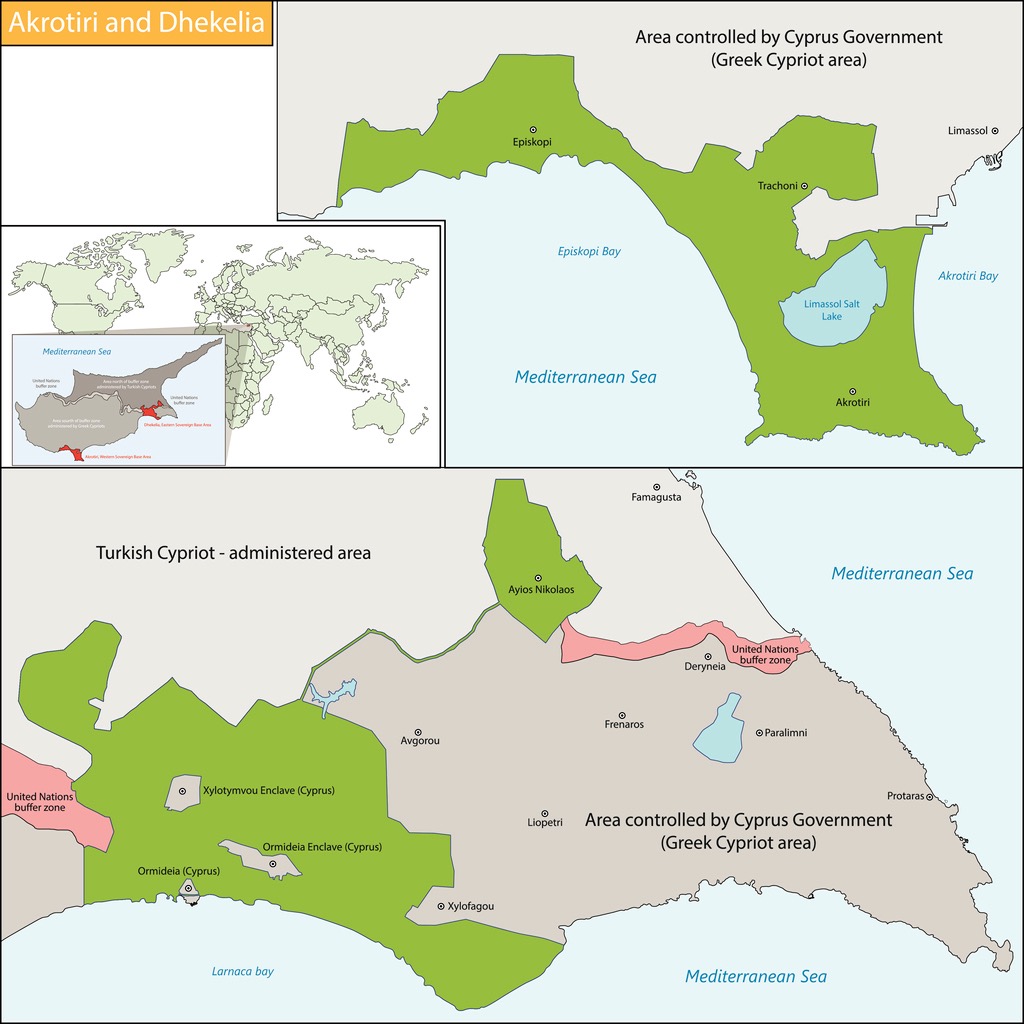

The United Kingdom, for example, is a Guarantor Power and has a responsibility to uphold the 1960 Treaties. That it has not by recognising the Greek Cypriot-controlled Republic of Cyprus as the official government is purely pragmatic, as it helps the British to maintain and protect their interests on the island, namely their two military bases, in Dhekelia and Akrotiri.

The British government is very much aware that the current wholly Greek Cypriot controlled Republic of Cyprus is not legitimate given the 1960 requirements. Yet, for matters of practical expediency, the UK, like other States, will recognise “governments” if they are in effective control of a state, irrespective of its legitimacy.

The British put their bases above the need for addressing the illegitimacy of the Republic of Cyprus

For the same reason, despite the existence of such illegality and a clear lack of legitimacy, it was also inevitable that the UN would recognise the Greek Cypriot administration as the government of the Republic of Cyprus, as the UN needs a host government with whom it can engage with to run its peacekeeping operations.

The fact that Greek Cypriots were the majority community in Cyprus and in effective control of the island’s territory also helped. Equally, it was also inevitable that Turkey and Turkish Cypriots would not accept and recognise an exclusively Greek Cypriot administration as the lawful Government of the Republic of Cyprus, and that they would fight against this state of affairs.

In short, the current Government of the Republic of Cyprus not only lacks the overall legitimacy, especially in terms of its claim to represent Turkish Cypriots, but also is devoid of any legality established in the international treaties which gave birth to the State in the first place.

For the past 59 years, the State of the Republic of Cyprus has been sitting on top of a series of illegal acts, which do not seem to bother any other country except the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus, formed by Turkish Cypriots in response to the ongoing denial of their political rights, and Türkiye which is the only guarantor power that remains to our day steadfast for the protection of the power sharing rights of the Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus.

This article is adapted from a thread Metin Topcan posted on Twitter on 15 Nov. 2022, in response to a statement by the Greek Cypriot Ministry of Foreign Affairs. You can follow Metin on Twitter / Mtopcan02

The main image, top, is of a statue in Nicosia of Archbishop Makarios – the first president of the Republic of Cyprus. Photo © trabantos / iStock