One of the best ways to learn a foreign language is to delve into a country’s history and learn about the incredible figures who played a pivotal role in shaping their nation’s future and identity.

One such person is Juana Azurduy de Padilla, a South American female general who went into labour, gave birth and returned to lead her cavalry into battle. She not only captured the Spanish standards, but she also won a famous victory all in the same day.

For many this may seem a little far-fetched, the stuff of legend, but it is in fact a true historical story.

Juana Azurduy was born in 1780 and died in 1862. Also known as Juana Azurduy Padilla, “la mujer general”, she was a South American leader who fought for independence from Spanish rule in the early 19thCentury.

Juana Azurduy was born in Chuquisaca, in what is now Bolivia. At that time, the territory was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, a huge Spanish colony that covered areas that today fall under Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

Juana was mestizo, or mixed race, by birth, with a Spanish father and an indigenous mother. After the death of her father, she was raised to be a nun in a convent, but was expelled at the age of 17 for her independent and rebellious behaviour.

The young woman had a great love and appreciation for the indigenous people of Bolivia and, in addition to Spanish, she also spoke other South American languages, including Quechua and Aymara – the main indigenous languages of Peru and Bolivia.

In 1805, she married her childhood friend and neighbour Manuel Padilla, a man who shared similar passions. The couple had four children together. By the standards of that period, their marriage was remarkably progressive, with Padilla standing by his wife on and off the battlefield.

Two of their sons, born before their parents’ military commitments began, would tragically die young from disease and malnutrition in military camps.

When Bolivia’s War of Independence began in 1809, both Juana and Padilla immediately joined the revolutionary forces and went on to command a 2,000-strong guerrilla army fighting the Spanish.

Padilla was later appointed civil and military commander of an area around Chuquisaca and by 1813 his army numbered almost 10,000 soldiers.

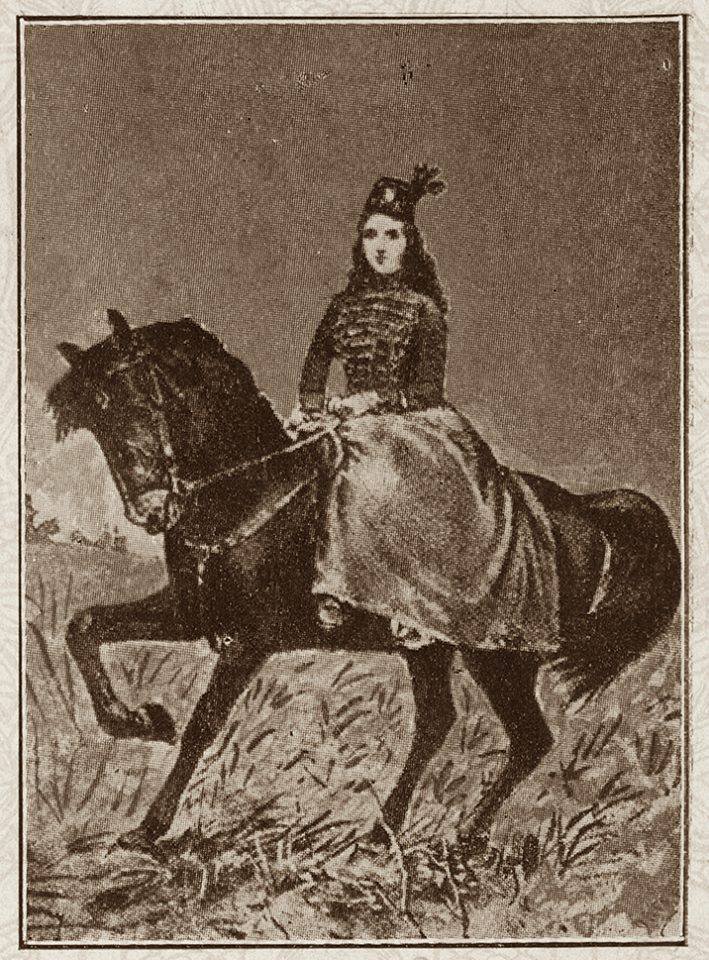

Between 1811 and 1817, Juana fought 23 battles as part of the war effort to liberate her people. During this time, she dressed in the uniform of a male cavalry officer, keeping her horse under a military cap, and became skilled at fighting with swords, rifles, and cannons.

On 8 March 1816, the forces under her command captured the Cerro Rico de Potosí mines, which was the main source of Spanish silver, and also one of the largest silver mines in the world.

During the battle, Juana personally led a cavalry charge that captured the enemy standard. For these acts, she was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was personally honoured by General Manuel Belgrano, who presented her with his own sword. In fact, General Belgrano was so amazed by Juana’s courage and skills that he gave her full command of the “Macha” legion.

Juana’s ability to “fight like a man” impressed the troops, and her valour, courage, and good sense ensured their loyalty. She had organised the “Leales” battalion in 1813, commanded the “Húsares” cavalry unit in 1815, and was often accompanied by a personal guard of 25 women, called “Amazonas”, each one a highly disciplined, courageous and fierce fighting woman.

During the Battle of Pintatora, in 1815 Juana went into labour and had to leave the battlefield to give birth to her fourth child. In an act that would become legendary, a few hours later she returned to the battlefield and led her troops, personally capturing the banner of the defeated Spanish forces.

On March 3, 1816, near Villa, Bolivia, this incredible female military commander led her cavalry, including her Amazonas, to attack the Spanish forces at La Hera. The women captured the Spanish banner and a valuable cache of rifles and ammunition that they desperately needed.

If Hollywood made a movie like this, many people would probably say it was stretching our imagination to its limits, but in Juana’s case it was a reality.

Sadly, Juana’s successes came at a great personal cost. During the Battle of La Laguna in September 1816, Juana was pregnant with her fifth child. Juana became injured, and in an attempt to save his wife, Padilla was shot and captured by Spanish forces. He was beheaded by royalists on September 14 and his head was mounted on a pike in the town of Laguna.

Juana found herself in a desperate situation: single, pregnant again, and with royalist armies effectively controlling the territory. With Padilla’s death, the northern guerrilla forces disbanded and Juana was forced to survive in the Salta region.

She led a counterattack to retrieve her husband’s body. The Spanish launched strong counter attacks against Bolivian forces in 1818, however, and Juana was forced to withdraw with her forces to northern Argentina. Here she continued to fight the Spanish with an army of 6,000 soldiers.

In 1825, after the withdrawal of the Spanish forces from Upper Peru (now Bolivia), Juana requested help from the independent government to return to her hometown, newly renamed Sucre, after Marshal Sucre. Juana was 45-years-old at the time, and had been fighting since 1809.

In 1825, the independent government of Simón Bolívar granted Juana Azurduy a colonel ‘s military pension. After visiting Juana to praise her service, Bolívar told Marshal Antonio José de Sucre:

“This country should not be called Bolivia in my honour, but Padilla or Azurduy, because they fought and made it free.”

In 1825, Bolivia declared its independence and Juana was able to return to Chuquisaca. Unfortunately, over the course of time her efforts in these vital wars were largely forgotten.

In her old age, Juana adopted an indigenous boy named Indalecio Sandi, who took care of her. It’s not clear what happened to her fifth pregnancy, and whether the baby was born. It is known that of her four children, only Juana’s youngest daughter survived the war.

The mother and daughter travelled to Salta to ask the Bolivian government for the return of Padilla’s properties, which had been seized by the Spanish during the war. It appears Juana’s attempts were unsuccessful. which would explain her poverty in later life.

Shockingly, in 1857 when Juana was 76-years-old, her pension was revoked during the so-called ‘bureaucratic rearrangement’ under the government of José María Linares. She died six weeks before her 82nd birthday, totally alone and impoverished.

Juana died on 25 May 1862, and was buried in a mass communal grave. Her courage and sacrifices helped Bolivia gain independence only to be defeated in old age by immoral politicians.

The memory of this incredible woman has been revived in recent times. Her remains were exhumed 100 years after her death and transferred to a mausoleum built in her honour in the city of Sucre, the official capital of Bolivia.

The President, Evo Morales, announced Juana’s birthday, July 12, as the “Argentine-Bolivian Fraternity Day”.

Today the airport in Sucre is named Juana Azurduy de Padilla International Airport, after the country’s former female warrior leader. The province of Azurduy in Bolivia is also named after her.

Posthumously Juana was also awarded the rank of general in the Argentine military.

Although her final years were devastatingly hard, these acts of recognition ensure that Juana’s memory is eternal. As her legendary accomplishments befit, she is now remembered as a national heroine of both Bolivia and Argentina.

Juana Azurduy part of trio displayed on Bolivia’s 100 pesos banknote

#Video

Conoce las características del nuevo billete de Bs 100, que entró en circulación hoy. El billete, según el BCB, cuenta con mejores medidas de seguridad, además de personajes históricos como Juana Azurduy de Padilla, Alejo Calatayud y Antonio José de Sucre.@BancoCentralBO pic.twitter.com/G6n4TGpPra— Página Siete (@pagina_siete) January 15, 2019

The legacy of Juana Azurduy, a free spirited woman of immense courage who helped liberate her nation from oppressive Spanish colonial rule, is proof that women when given the opportunity can and do achieve the highest levels of greatness.

The man revoked Juana’s pension, José María Linares, unwilling to remain in power through democratic means, turned in 1858 to dictatorship. He ruled all by decree, and regularly used force of arms, ostensibly to restore order, but more usually to suppress legitimate protests and uprisings.

Linares’ behaviour was a contradiction of everything he had always claimed to stand for, and unsurprisingly, he became very unpopular.

In January 1861, Linares was overthrown as a result of a coup d’état sponsored by his own Minister of War. He was later banished to Chile, where he died that same year.

Main image, top, of Juana Azurduy statue in Buenos Aires, Argentina, May 2019. Photo © Patricio Hellstrom /shutterstock