On 20 May 1897, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Greece reached an armistice after a month-long war. The war was one of several conflicts between the Ottomans and an irredentist Greece.

The Kingdom of Greece for its part had been established in 1832 when Russia, Britain, France and Bavaria brought the young Greek Republic under their protection and guaranteed its sovereignty by enthroning Prince Otto, the teenaged son of the Bavarian ruler Ludwig I. The campaign for Greek independence from the Ottomans had begun over a decade earlier in 1821.

In spite of these developments however, many Greeks continued to live in the Ottoman Empire until its demise. Some worked as public officials and participated in the business of imperial government such as Mousouros Paşa who served as the Ottoman ambassador to Britain and other European countries.

These Greek subjects had benefited from the liberalising reforms of the Tanzimat period (1839-1876) that had been introduced by the Ottoman Government, emancipating non-Muslim subjects as equal citizens to their Muslim counterparts. Some Ottoman Greeks had also left the empire to live in the independent Greece, but became disillusioned by their experience of Athens and ultimately moved back to their former homes in prosperous Ottoman cities like Smyrna (Izmir), Salonika (Thessaloniki) and Constantinople (Istanbul).

Emancipation and prosperity however would not satisfy all Greeks on either side of the borders, and the 1897 Greek-Ottoman War would not be the only conflict between these powers over lands and populations. Others would later include the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, during which Greece captured Salonika, the birthplace of Turkey’s founder and first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Atatürk played a major part in shaping the territories of Turkey & Greece

Atatürk himself would play a principal role in another of these conflicts following the First World War. He would lead the remaining components of the Ottoman army in the Turkish War of Independence, or National Struggle of 1919-1922, after which the Turkish Republic would be triumphantly built on the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. And when Atatürk’s victory was recognised by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, population exchanges between Greece and the Republic of Turkey would see both sides swap the majority of their remaining Muslim and Greek populations respectively.

Yet when the Greek-Ottoman War of 1897 began, the young Mustafa Kemal was in his second year at the military high school in Manastır, now Bitola in present-day Macedonia. There is a legend however, that he fled the school to volunteer amid the high nationalist sentiments among Ottoman Muslims when the war was declared in mid-April and was turned back on the way by his mother Zübeyde.

At this time however, Turkey or the Ottoman Empire as it then was, was headed by another famous and decisive leader, Sultan Abdülhamid II, remembered as the “last great sultan” by his supporters and a “regressive despot” by opponents. Sultan Abdülhamid remained on the throne from 1876 until 1909, but effectively lost his power in 1908 with the Young Turk Revolution when a set of nationalist officials seized power and reduced him to a constitutional monarch before deposing him the following year.

This sultan’s reign was surprisingly, a relatively peaceful one, at least when it came to conflicts with external powers. While his rule began with a war against Russia in 1877-1878, which saw the empire lose a significant share of its European territories, the sultan quickly learned that sustaining peace with neighbours and Great Powers would be the best way to preserve the territorial integrity of the Ottoman State. Indeed after a peaceful spell in the 1880s, except for internal conflicts with Armenian nationalists in Anatolia in the early 1890s, the spectre of conflict would not raise its ugly head again until the 1897 war with Greece.

Nationalists drive “Megali Idea” for a ‘Greater Greece’

The war’s roots are to be found in Greek nationalist irredentism and ambition to unite the Kingdom of Greece with large swathes of Greek-populated territory that had remained part of the Ottoman Empire following Greek independence. This plan, known as the “Megali Idea” or “Great Idea”, was to form a Greek Empire. The island of Crete, then under the Ottomans, was central to the start of the conflict.

When fresh Greek rebellions broke out in 1895, Sultan Abdülhamid responded by switching the island’s governor, appointing a Greek governor to appease the unrest. When Muslim subjects protested against this, he again switched governor, this time to a Muslim official, the Greeks responded in kind by calling for unification with mainland Greece.

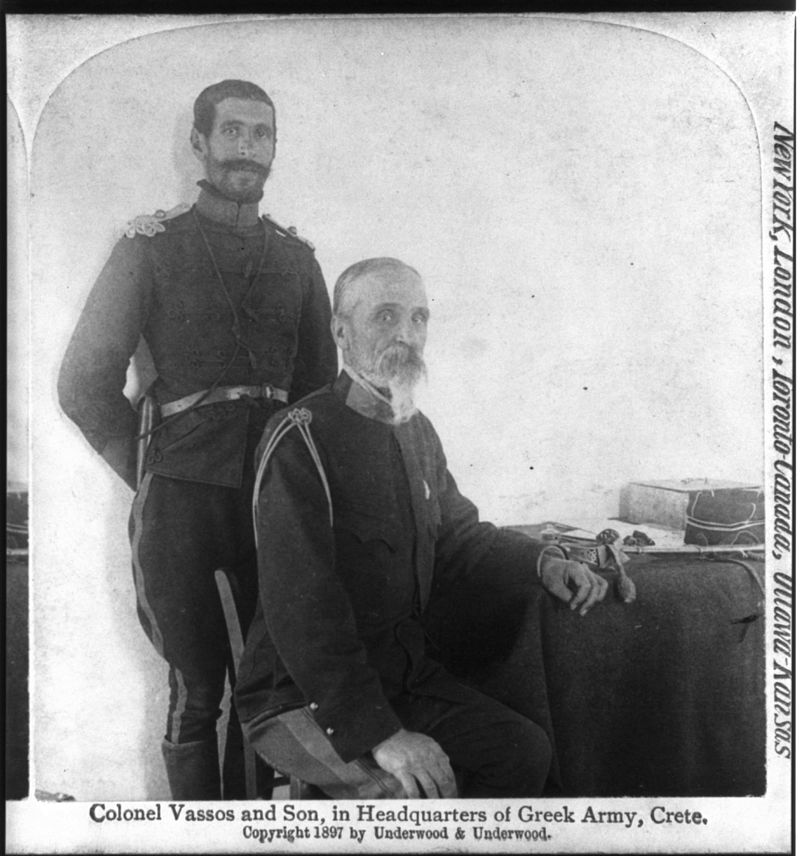

The Cretan Greek rebels continued their insurgency through 1896 making the island increasingly ungovernable. In 1897, these insurgents called for support from Athens who responded by sending troops to the island. This move was opposed by the Western Powers who demanded that the Greek forces withdraw in return for the Ottoman Government’s granting the island autonomy which would leave it only nominally under the sultan’s rule.

Athens, however, did not heed the Western Powers’ calls and was instead carried away by the irredentist fervour of the influential Ethniki Hetairia (National Society), an organisation that advocated the absorption into Greece not only of Crete but also other Ottoman territories such as Epirus, Thessaly and Macedonia.

The Ethniki Hetairia’s volunteers including Greek soldiers began to gather at the Greek-Ottoman border at Thessaly forcing the hand of the Greek Government to mass its own forces there too. By February 1897 around 25,000 Greek troops were ready to invade the Ottoman Empire.

Germans help modernise Ottoman military

Constantinople declared war on Greece on 17 April following several raids across the border by Greek volunteers. The war ended quickly with a decisive Ottoman victory in just over a month. The Ottoman military, reformed for much of the nineteenth-century, had been undergoing further modernisation with European assistance, coming mainly this time from Berlin.

The German General and later Field Marshal, Colmar von der Goltz for example had been heavily involved in improving education at Constantinople’s Military School known as the Mekteb-i Harbiye, and served in the empire from 1883-1895; he would also later return in 1908 and in 1915-1916. What’s more is that over the course of the 1880s, the Ottoman Empire had also purchased much up-to-date military hardware from Germany. These developments meant that at the start of the war in 1897, the superior Ottoman forces were better equipped and trained than their Greek counterparts, smashing through Greek lines and heading south.

As the Ottoman advance continued, Europe’s Great Powers began to exert pressure on both Constantinople and Athens to end the conflict. In response the Greeks withdrew their forces from Crete and the Ottomans stopped their push further into Greece.

An armistice was ultimately reached and although the Ottoman Empire was not permitted to keep the territory it had captured, it was awarded with a large sum in reparations from Athens and Crete was allowed to remain Ottoman in name. The Ottoman victory also presented Sultan Abdülhamid with a great opportunity to add to his prestige as a holy warrior or ‘gazi’, making him popular among his Muslim subjects and sending a firm message to internal opposition groups and secessionist Balkan agitators.

European Jews court Sultan for homeland in Palestine

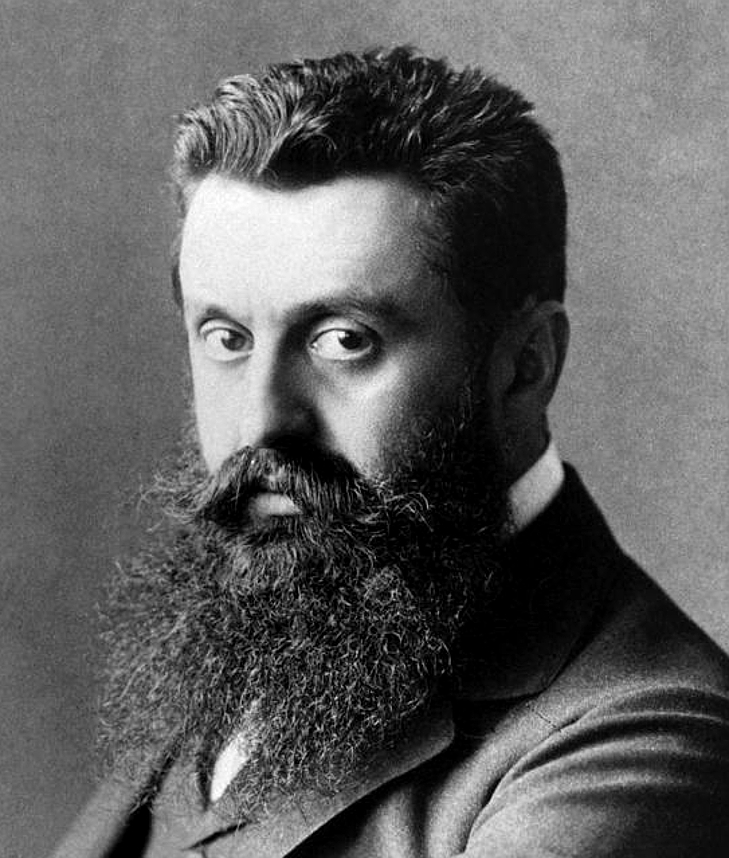

While the Ottoman victory presented the sultan with an opportunity to improve his reputation publicly, the war itself was also seized as an opportunity by foreign political activists. Having witnessed increasing European anti-Semitism, Theodor Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian Zionist leader, intellectual and journalist concluded that the Jewish people would need a state of their own outside of Europe if they were to survive and prosper free from prejudice and persecution. Though he had considered several locations for this state at various stages in his career including Argentina, Sinai, Uganda and Cyprus, Herzl’s preferred and firmest choice was naturally the Jewish ancestral home of Palestine, then a part the Ottoman Empire.

During the war, seeing an opportunity to demonstrate the friendly disposition of the Zionist movement toward the sultan, Herzl actively supported the Ottoman cause in the hope of currying favour with Constantinople and attempting to convince the Ottoman Government to allow the Zionists to establish an autonomous Jewish state-let within the empire.

Though Herzl’s efforts with the sultan were ultimately unsuccessful, he was indeed able to raise humanitarian funds for wounded Ottoman soldiers from Jewish figures and organisations both in France and Austria-Hungary, and helped to organise a group of Jewish medical students who had volunteered to support the Ottomans on the battlefield. These students, however, would not receive their travel funds until after 30 May that year, missing the armistice.

All in all, the Greek-Ottoman War offers a unique window through which we can observe many dimensions of the history of the Ottoman Empire. This includes the lives and experiences of its citizens, the role of ethno-linguistic nationalisms in the Empire’s demise, its relations with European Powers and organisations both positive and negative, and the reign of its last decisive sultan.