Late last month, Trump Administration Secretary of Defense James Mattis touched down in Ankara on a tour of Middle Eastern and Black Sea capitals. The Secretary’s Turkey visit, part of a trip that also included stops in Amman, Baghdad, Erbil and Kiev came as an effort to smooth out feathers already ruffled in the often tense American-Turkish relationship.

After a 90-minute meeting with his Turkish counterpart Nurettin Canikli at the Defence Ministry, Secretary Mattis was received for half an hour by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during his day-long stay on the 23 August.

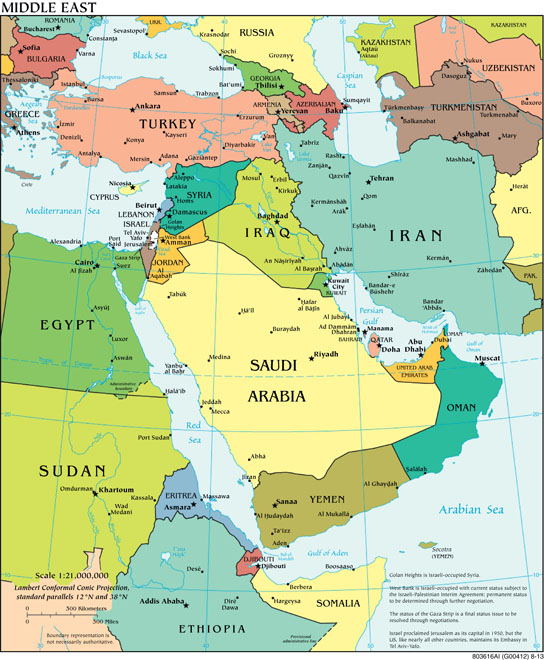

Talks focused primarily on neighbouring Syria and Iraq. At present, American support for Syrian Kurdish militants, the People’s Protection Units or YPG, has driven a difficult wedge between Turkey and the US. Ankara’s concerns are based in the fact that the YPG is linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which has waged an armed secessionist campaign against the Turkish State since 1984 and has been designated a terrorist organisation by Turkey, America, the United Kingdom and the European Union. The US has made efforts to play down these links by re-branding the YPG as part of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” (SDF), a coalition of American-backed Arab and Kurdish surrogate fighters participating in the campaign against the Islamic State (IS) stronghold of Raqqa.

Ankara views the YPG and PKK as one in the same and is anxious that American arms will cross its border from Syria and be used against Turkey. This poses the danger that the country’s internal conflict, which has cost tens of thousands of military and civilian lives since its inception decades earlier, will intensify. This fear has been exacerbated by the autonomous cantons established within Syrian territory by the YPG’s political wing, the Democratic Union Party or PYD. These cantons have stoked concerns in Ankara that their presence may have a seditious effect in encouraging similar sentiments to spill over into Turkey’s significant Kurdish minority, which makes up around a fifth of the country’s population.

Yeni Şafak’s Tamer Korkmaz: “The US isn’t our ally, but enemy”

American support for the YPG and the accompanying risk to Turkey has produced fierce backlash in the Turkish press. On 6 June, Tamer Korkmaz a columnist at the right-leaning Yeni Şafak newspaper for example, wrote a provocative piece with the headline: “The US isn’t our ally, but enemy” in which he added “Every terrorist attack by the PKK is actually a terrorist act by the U.S.”

The Trump Administration has sought to allay these concerns with the Defense Secretary’s visit. According to sources quoted by the Washington-based Middle East news site Al Monitor, Mattis discussed providing Ankara with assistance “mainly on the intelligence and targeting side” against the PKK in the Sinjar area near the Iraq-Syria border and the Qandil Mountains between Iraq and Iran during the talks with Turkish officials. Whether this support will actually materialise is another question, especially given America’s reliance on the YPG in Syria, which could mean the US Government would be anxious about any moves that might create rifts between itself and its proxy.

For now however it is difficult to tell whether this gesture from Washington has restored any of Ankara’s lost confidence in the troubled partnership between the two NATO allies. No joint statements were released following the talks nor was there a press conference. After giving us that little to go on, this could indicate that the two sides were unable to agree on anything strong or workable going forward. With their differing and at times conflicting strategies regarding how best to defeat IS and resolve the Syrian Crisis, greater divergence between the two sides over the Middle East is simply a fact of the current US-Turkey relationship. This reality was especially hammered home after American forces exchanged fire with Turkish-backed Syrian rebel groups on 29 August.

There was at least one issue on which both sides did agree during the talks though, namely the importance of Iraqi territorial integrity. This subject has been raised by plans for an independence referendum scheduled for the 25 September by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Northern Iraq; the KRG is a firm ally of both Turkey and the US (whose own Peshmerga forces have also had their own armed clashes with the PKK and others aligned to it). Yet while President Erdoğan stated following the talks that “to declare formal independence from Iraq would be a wrong step” the American delegation’s statement did not mention the referendum explicitly.

Nonetheless, though Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu tried to discourage independence on an official trip to Iraq’s Kurdish capital of Erbil on the same day as Mattis’ Ankara stop-off, he also informed Kurdish President Masoud Barzani that it would have “nothing to do with our trade in this Region,” implying that Turkey would not close its border with the KRG in the event of a pro-independence vote.

Iranian Chief of Staff General Bagheri’s visit to Ankara in mid-August was ground-breaking: the first of its kind since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution

One final important factor discussed during the Defense Secretary’s visit was the role of Iran in Middle Eastern affairs, referred to in the US statement as a “malign influence in the region”. US concerns about Iran may well have been linked to the Trump Administration’s recent overtures to Turkey, especially after the high-profile Iranian military official, Chief of Staff General Mohammad Hossein Bagheri was hosted in Ankara for a three-day stay in mid-August. As the first of its kind since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, Bagheri’s visit was ground-breaking, symbolising a degree of détente between the two regional rivals.

What’s more, both Turkey and Iran are increasingly seeing eye-to-eye on a variety of challenges facing the Middle East. As a host to its own Kurdish minority and a close ally of Iraq’s Baghdad Government, Iran is also wary of Kurdish bids for independence in its neighbourhood. In this vein, as a strong regional power, Tehran is uniquely situated to partner with Ankara in addressing their shared anxieties relating to Kurdish secessionism and militancy of varying stripes, and has already been making steps in this direction. One of the major points of discussion when Bagheri met with Turkish officials last month was potential co-operation against the PKK and its Iran-based affiliate the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK).

The continuing Gulf Crisis has also presented another area in which the two countries’ alliances intersect. Both Turkey and Iran have been vocally supportive of Qatar, which has been isolated and blockaded in its surrounding area since Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt cut diplomatic ties with the country on the 5 June. The four took action against Qatar on the basis of its warming ties with Iran and its support for movements that they deem “terrorists”, such as the Muslim Brotherhood.

Qatar and Iran–which has in recent years engaged in a cold war with Saudi Arabia for hegemony in the Middle East–are bound together by the fact that their territorial waters include the world’s largest natural gas field, the exploration rights of which they share. The two restored diplomatic relations fully last month and are seeking to expand their relationship in all sectors.

Turkey’s alliance with Qatar means the Turks can demonstrate their own hard power in the Gulf

Turkey–whose governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) views itself in some ways as a fellow traveller of the Muslim Brotherhood (particularly in Egypt), in the sense that both have religiously conservative outlooks and have pursued the governance of their respective countries by contesting elections–has also been sympathetic to Qatar for its friendlier approach to the movement. Ankara and Doha share strong business ties, including a great deal of Qatari investment in Turkey and increasing bilateral trade, which according to Turkish Customs and Trade Minister Bülent Tüfenkci has tripled since the start of the crisis.

Moreover, Turkey’s alliance with Qatar also allows the country to demonstrate its own hard power in the Gulf region with its military base on Qatari soil; importantly, the Turkish Parliament confirmed a military agreement allowing for Turkish forces to be deployed in the country just two days after the crisis began. The closure of the base is among a set of 13 demands made by the Saudi-led bloc to be met if the two sides are to reconcile.

This crisis has pushed Iran and Turkey closer together, both of whom have been shipping tons of food to Qatar to help ameliorate damage caused by the sanctions. Both countries are seated rather firmly in the pro-Qatari camp and their goals and interests appear to be overlapping increasingly. While it is unlikely that Iran could replace the US as Turkey’s main ally despite some serious policy divergences, on Middle Eastern affairs however, it appears that Ankara and Tehran are well-suited to partner effectively on several fronts.

Main photo: Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan meets with US Defense Secretary James Mattis in Ankara, 23 Aug. 2017. Photo © DHA